Review: A Promising Young Woman and the End of the Girlboss Era

Spoilers included to protect people from the experience of watching a terrible movie. (content warning: sexual violence against women)

When so much of life is organized around dodging male violence, it’s nice to relax with a movie in which the only source of violence is a woman, and the only target is a man, or many men. It doesn’t matter what he did. He probably had it coming.

Rape revenge films sometimes spare us the trauma of the assault, but they never spare us the satisfaction of seeing the assaulters sliced and ruined. This is what makes them so thrilling: the fantasy that after an assault there can be a clear and gratifying course of action; that female wrath, undeterred, can restore something by taking something; and that there exists not only a commensurate level of pain to inflict, but that the wronged can inflict it. Emerald Fennell wouldn’t agree.

In an interview with Vulture, she says, “I think actual anger, real anger, makes me feel ill, really ill… For me, it’s not pleasurable and the release of it isn’t pleasurable. It’s frightening.” No wonder her film, Promising Young Woman, advertised as a “cheeky #metoo rape revenge thriller,” was none of those things. That has not stopped film reviewers from insisting that it “embodies rage” and “retribution.”

Promising Young Woman was released earlier this year and has since been nominated for four Golden Globes and five Oscars. In her rush to claim her crown before the Me Too movement stopped trending, it seems Fennell did not waste time developing her main character or the plot. The production company “fast tracked the feature.”

The protagonist of Promising Young Woman is named Cassandra. She’s living with her parents and works at a coffee shop. We meet her the same way the trailer introduces her—pretending to be drunk and taken home by a ‘nice’ guy played by Adam Brody. You know what happens next: Cassie’s completely ludic interrogative, “what are you doing?” After that, nothing. We cut to the morning after, red dripping ominously down Cassie’s leg as she walks home. It is just ketchup from a hotdog. This fake-out accurately represents the movie to come, it looks cool but upon closer inspection reveals itself to be a gross mess.

While Cassie and her best friend Nina were in med school, Nina was raped in the middle of a party. A horrifying assault that we later learn was filmed, complete with the sound of her classmates laughing off camera. We aren’t told whether it was the trauma of the assault or the confident disbelief of everyone around her that pushed her to take her own life. But she does, and Cassie drops out. Does Cassie, who it’s emphasized was a top student, use her medical knowledge to punish those responsible with the flair of a future surgeon? No. Fennell says, “ [the] thing with the revenge [genre] that we don’t talk about very much is revenge and vengeance aren’t good things.” This isn’t a view supported by thesis of the film. Incoherently checking off every over-heard talking point regarding ‘rape culture’, the film promises a take it never gives. And still mishandles the genre conventions to which it is indebted.

Our heroine Cassie is an “angel of revenge” written by someone who doesn’t believe in revenge. As a result, the film offers no thrills. What it does do is punish women, absolve men, and let the cops handle the rest.

The aversion to any violence against men doesn’t come from a commitment to reality. The heroine has, for what seems like years, gone to bar after bar alone, been taken to bed by strangers who prey on the drunk, and escaped with apparently no consequences beyond getting home late. Neil is the second cliched archetype of pretentious“nice guy” who takes her home. When he molests her while she’s pretending to still be drunk, her response is to scold him for not “even knowing her last name” and then leaving. Why the beatific restraint in a movie described as “sexy” and “provocative”? Because, according to Fennell, “the thing about anger in anyone — but I suppose more specifically in women — it’s not sexy or glamorous, you know?” Well, neither is admonishing assaulters with the tone of a disappointed school teacher (at least not in wide release films).

The film demonstrates over and over again just how little power Cassie has, how limited her spheres of influence are. She moves listlessly from her childhood bedroom to bars to the coffee shop counter she works at. Her motivations are vague and unsatisfying. She is clearly grieving her best friend. But without the logic of revenge, Cassie’s actions are given neither meaning nor do they communicate a purpose. Her pretense of drunkeness offers no security or advantage. She doesn’t even carry a weapon.

The only people Fennell believes are worth punishing are women. Cassie visits three figures connected to Nina’s rape: Dean Walker (Connie Brittan) who sided with the assaulter, Madison (Allison Brie) who did the same by remaining friends with the assaulters, and the lawyer (Alfred Molina) who successfully defended the rapist. She misleads Madison into thinking she’d been assaulted by getting her drunk and leaving her to wake up in a hotel room with a stranger. Cassie misleads Dean Walker into thinking her daughter is at risk of assault by kidnapping the young girl, leaving her at a diner, and telling the mother she was at a frat house. This naturally terrifies Dean Walker. She’s forced to admit the threat of sexual violence on college campuses, something she denied happened to Nina. Before we can process the efficacy of this gesture, Cassie is taking a crowbar to a stranger’s car. I would have rather seen the crow bar on the occasions men were trying to force themselves on her.

If the intended point was that the people connected to the rape weren’t sufficiently effected, then that too needed to be shown. Instead it was stated, then quickly made inconsequential. The lawyer is forgiven in the same scene we, and Cassie, meet him. The exoneration is narratively moot — a net zero on emotion, meaning and relevance to the plot.

What’s worse, like the trailer, the forgiveness scene too hints at a more interesting film that could have been but wasn’t. The lawyer mentions he was incentivized to defend college rapists, that they were easy cases that made his firm rich. I wondered then, if the lawyer and Cassie would team up to rectify that history, with the lawyer now at her mercy. Instead Cassie begins dating her former classmate, Ryan.

We later learn Ryan was part of the group that watched, and laughed at, Nina being raped. This revelation causes Cassie to puke and break up with Ryan. Every scene, from Cassie’s conversations with her parents to her final monologue, is emotionally vacant yet musically scored for actions that aren’t occurring. Plenty of material for a cool trailer, not a film with any dimension. It’s easy to see that it was written quickly, and inspired mainly off a description of what would become the trailer. In the background you can almost hear Fennell planning the pull quotes for her film press.

Eventually, Cassie learns the man who raped her friend is having a bachelor party. She misleads the men who attend into thinking she’s a stripper. Little do they know she’s actually...a woman in a stripper costume.

At the party, Cassie leads the rapist to a private room, where she’s quickly overtaken and slowly throttled — but not before the aftermath of a real life campus assault is crudely referenced in a monologue that becomes corny in addition to tasteless as we watch the protagonist suffocate, writhing under a pillow held over her face. I wonder how reviewers would have responded if a man had made a film in which a woman, traumatized by the assault and death of her friend, is murdered by the same man that committed the assault, shot with pornographic dedication to the sensation of a man’s full weight channeled through a knee holding a pillow over a sex worker’s face. Cassie’s death lasts exactly as long as it would take for a woman to actually die this way, two and a half minutes. Fennel learned this from her father in law, an ex cop.

Statistically speaking, cops are more likely to be assailants than resources. Most recently in Fennell’s home country cops were quelling protests over a murder of a woman which, like many others, was committed by a cop. In this film, it is the cops who rush in to save the day and deliver the conclusion.

Anticipating her death, Cassie had given her work friend instructions for where to look if she went missing. This leads the police to arrest men from the bachelor party after they recover Cassie’s body, which we had to watch burn into the ground. (Do let me know if you know whether that scene was supposed comedic or tragic, because it committed to neither category.) Meanwhile the heroine starts as a victim (centered in the aftermath of a friend’s trauma) and ends as a victim (killed by her friend’s rapist.) Given the wealth and status of the men who are eventually arrested, one can assume they won’t spend much time in jail. And given the nature of her death, there’s plenty of precedent for it being excused as self defense.

I wanted to see men die, which is what the trailer teased, and why I’d been eagerly anticipating the film long before its release. Instead, I had to watch a woman be slowly, torturously killed, after wasting her time (and mine).

In my more generous moments I thought perhaps the film was trying an avant garde approach to a feature length episode of Law and Order — that the tonal incoherence might be redeemed by a final act of irony, which would reveal it all to be bad satire. Maybe the film would even register as camp in the future. But then Cassie’s posthumous timed text messages appeared on one of the culprit’s phones to gloat. “Enjoy the wedding”, it says, with “Love, Cassie & Nina” and a winking smile emoji. Cassie, by her own admission, did achieve what she set out to do. Which was, apparently, the radical praxis of alerting the authorities.

Review after review claims Promising Young Woman is a feminist triumph. Where exactly are they locating that triumph? History isn’t made by well behaved dead women. Confrontation is teased, but builds to an end that has no impact. The wholly unnecessary romantic subplot takes up most of the film, and is really just set up for a twist that is underwhelming (and a song sequence in a pharmacy that the editor rightly but unsuccessfully begged Fennell to cut). In case we missed it the first few times, Ryan’s character serves only to show once again that even clean cut white guys can be complicit in sexually violent crimes. Who is this movie for? It could have done more with the fact that “nice guys” also prey on vulnerable women, but like much of the film here too it chose only to briefly hint at subversion through the most obvious truisms and then carry on without actually subverting anything.

Promising Young Woman has been positioned to sweep awards season, revealing how eager Hollywood is to reclaim its image after the scandal of Harvey Weinstein. I suppose it’s one way to avoid another red carpet with outfits ruined by actors and abusers alike wearing pins of solidarity. What a relief it must have been to procure a movie described as provocative and feminist whose politics would still be familiar to the aging voting body of the Academy. To my disappointment, and apparently the approval of many others, no one powerful in the film suffers anything close to commensurate with the violence they’re complicit in. You know whose anxiety is most palpably communicated by this film? Ryan’s. He’s terrified at what the tape of the assault might do to his reputation.

The violated woman, having killed herself, is removed from society, subsequently positioning rape as an experience one is both defined by and cannot survive (a message the women in my life who have been raped did not appreciate). The people who supported the rapist experience little in the way of retribution beyond embarrassment, some social awkwardness, and maybe a blemish on their records. This certainly is someone’s fantasy, but it isn’t a subversion of reality. The lawyer who successfully defended the rapist even receives absolution, for no reason other than the fact he privately confessed to feeling guilty — making Promising Young Woman less a feminist rape revenge thriller and moreso a big budget Catholic school special. The depiction of Cassie’s assault and death is lingeringly graphic, as has always been the standard for Hollywood. And her emotions are so underwritten that they appear to be irrational. It’s hardly a win for the cause. If the film wanted to comment on the injustice of how little retribution rapists and those complicit face, then why position Cassie as a “badass” who finds satisfaction? Watching the movie limp from one unsatisfying confrontation to the next, scored as if something dramatic and moving was happening, felt a lot like being gaslit. As did its reception.

I’m willing to accept anyone’s defense of the movie’s heavy handed visual metaphors, commitment to centered shots, even the cloying cover of Toxic that scores Cassie’s fatal jaunt to the bachelor party (another example of Fennell being so self satisfied at her aesthetic choices that it doesn’t seem she gave equal thought to the story itself). I cannot accept the invitation to celebrate it. Marketed with language once used in reports of campus assault, the movie is modern precedent appropriated, rinsed of its power to name abuse, and grafted onto a conservative ideology confidently being pushed onto the future.

More explicitly, it takes its title from Brock Turner, a rapist described as a promising young man by the very people this film trusts to dole out the final acts of justice. In case there was any doubt exactly which cultural moment this film sought to benefit from, it puts itself in direct conversation with actual campus assault cases. The dialogue gratuitously pulls from platitudes about the double standards women face. Dean Walker says it’s every man’s worst nightmare to be accused of rape. She has to say this, or else Cassie wouldn’t get the chance to ask, “do you know what every woman’s worst nightmare is?” At least we were spared the Margaret Atwood quote.

According to the consensus around the film, I’m meant to believe that Promising Young Woman isn’t just a good movie, but a cultural victory for all women for no other reason than the fact that the film is both made by a woman and nominally about violence against women. Wouldn’t it be less sexist to not grade women on a curve?

Promising Young Woman succeeds, not as an illuminating commentary on campus assault, but as an exhibit of the existential tension between the victimhood white femininity depends on and the feminist cosplay it congratulates itself for. It is the perfect film for the death throes of a phenomenon best known as girlboss feminism.

As the rote dialogue of the film proves, social media transformed the public expression of feminism. Over the last few years a chorus of people have found community in commiserating the experiences that are common but, up until now, rarely discussed with a collective outrage in favor of the abused. And because we know how the preexisting public trial systems (both official and not) fail us, there is an urgency to expressing our solidarity with the abused. It is out of this confluence of circumstances that the Me Too movement was born.

Despite its spark of democratic expression, the Me Too movement was quickly extinguished into something more politically neutered. By prioritizing public disclosure of personal trauma, catering to the voyeurism it attracted, and hinging on the type of victim a person was invited to be, it was near perfect for the narcissistic impulses of girlboss feminism.

Girlboss feminism lacquers any self/status-quo serving ambition with the claim that it’s in the noble service of advancing women, because it advances one woman, who is usually oneself. The most notable examples of this logic are the CEO’s collectively called Girlbosses, a term once encouraged by this same set of women and now used derisively against them. Monied and driven, these girlbosses are just...bosses. By nature, the executive suite has limited occupancy.

You can read profiles of these savvy entrepreneurs that made their millions while cheering themselves for doing so. The profiles include women who went on to sexually harass, underpay, and discriminate against women. Now too plainly hypocritical The girlboss era is thankfully over (or at least the magazine covers celebrating it are).

Late enough to be clocked as a girlboss, but just in time to be lauded for her feminism, writer and director Emerald Fennell offers a variation on the theme. Despite the narrative surrounding her directorial debut, Fennell is not exactly an underdog. The Oxford educated daughter of a famous designer is an experienced and well connected writer, showrunner, and actor. Her performance as Camilla Bowels in The Crown was superb. But season two of “Killing Eve,” for which she was the showrunner, displays the same preference for gimmick over story that would become the hallmark of her feature film.

For women advantaged by either money, access, reach, or some combination thereof, foregrounding their gender as their primary subject position insists there were stairs where they used an escalator. I do not doubt Fennell is intimately familiar with sexism and misogyny. In interviews about Promising Young Woman she often describes a film much better than the one she made, which indicates insight into her chosen subject or at least a savvy awareness of the current cultural conversation around sexual violence and female testimony. I know that being a woman inescapably shapes one’s experiences. But let’s be honest about what distinguishes those experiences from each other.

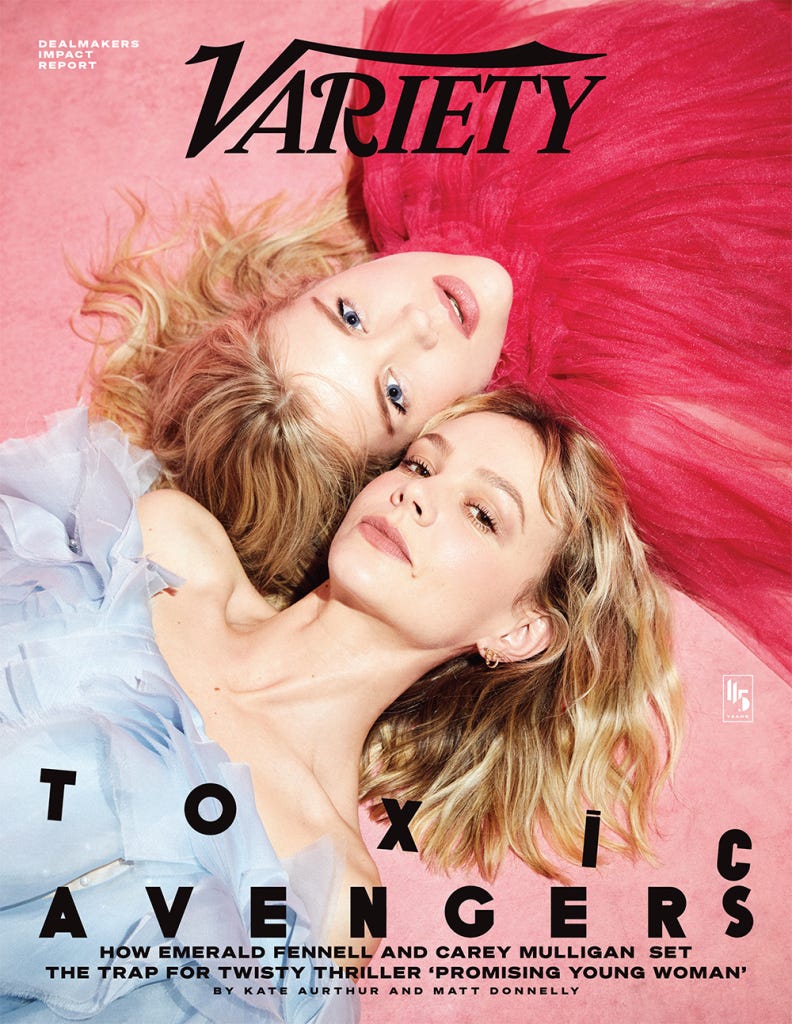

In the press run for Promising Young Woman, Fennell and Carrie Mulligan, the starring lead, repeat how significant it is this film exists at all. It was bought by the same studio that made I, Tonya and Birds of Prey, and is being distributed by one of the largest film studios in Hollywood, so I’m not sure just how bad its odds were. Like many rich white women before them, Mulligan and Fennell express great surprise at their own success while in the same breath describing enthusiasm from executives at every stage of the film’s development. Unlike movements in solidarity with global struggles against the physical and economic violence of men, white feminism does not have a political agenda beyond asking for a seat in rooms it’s already holding conferences in.

How does a politics dependent on victimhood achieve power? It doesn’t—which is why Promising Young Woman is so widely acclaimed. Like the Me Too movement it references, the film is mainstreamed, celebrated even, in part because it’s limited to the voyeuristic consumption of trauma and confessional politics of absolution—which is what white people assume occurs once they admit to privilege and what the powerful expect once they admit to guilt. Like a diversity statement “promising to do better”, this movie only acts like it’s challenging something, a mode that is so convincing in its delusion that Mulligan even chastised a film critic to the point of public apology because she felt his positive review unfairly appraised her performance by alluding to her appearance. The exact words she took issue with were:

“Mulligan, a fine actress, seems a bit of an odd choice as this admittedly many-layered apparent femme fatale...Cassie wears her pickup-bait gear like bad drag; even her long blonde hair seems a put-on. The flat American accent she delivers in her lowest voice register likewise seems a bit meta, though it’s not quite clear what the quote marks around this performance signify. Still, like everything here, this turn is skillful, entertaining and challenging, even when the eccentric method obscures the precise message.”

The review is accurate on everything except the performance being “entertaining”. And I’m not convinced the same complaint would have been leveled against a female author. Mainly because Margot Robbie, who produced the film, has on many occasions made the same observation as the film critic on Mulligan being the “odd choice”. When explaining why she didn’t take the role Robbie told reporters, “I just felt like I wouldn't be that surprising,” Mulligan, she says, was the unexpected choice. Fennell too has said, “Who I really wanted for the role was someone who was a surprising choice...Carey was top of my list.” To me it sounds like the critic was only picking up on the filmmaker’s and producer’s intention.

The allegedly sexist review has since been amended with an editor’s note declaring: “Variety sincerely apologizes to Carey Mulligan and regrets the insensitive language and insinuation in our review of “Promising Young Woman” that minimized her daring performance.” Perhaps wary of the same treatment, most reviews of the film couch their misgivings in effusive praise:

“Promising Young Woman” is as confident as its protagonist, a film that’s willing to be a little messy and inconsistent…a lot of the issues I had with “Promising Young Woman” almost feel like strengths now. I’m not sure the ending lands, and some of the tonal jumps could have been refined, but there’s so much movie here to unpack”

“a harsh film, rough and ready and daring as hell”

“A film with a strange tone...It's social commentary as art and it works.”

“A delicious comedic thriller with a stellar central performance“.

“..an itch for justice... is scratched by a twisted knife.”

Unless you count the scalpel that’s never used (because Cassie is killed before it can be), there are no knives in this film. There is no sexism in the pilloried Variety review. And there is no “feminism” “revenge” or “thrill” in this “feminist rape revenge thriller.”

No woman is allowed to be impressive in the film. And a woman who doesn’t believe in revenge, is admittedly afraid of anger, and uses cops as creative consultants did not deliver the “diabolically funny takedown of toxic masculinity” that the film is described to be. Sure, the film opened with male crotch shots designed to signal that this film was going to ‘flip the script’ by putting men on the receiving end of a lecherous gaze. But one sequence of watching men dancing and we’re forced to spend the rest of the film atoning.

Rather than punish rapists, the film addresses viewers as if they were children. When discussing their film both Mulligan and Fennell repeatedly use the same metaphor of a “poisoned candy”. Speaking to Variety Mulligan says, “It’s a sort of beautifully wrapped candy, and when you eat it you realize it’s poisonous.” Like the reporters that interview them, Mulligan and Fennell revel in what they feel is a deep contrast between the color palette and the subject matter. I wonder whether they feel we’re stupid, or they actually believe that this film is society’s introduction to the concept of irony. That what is pretty and sweet is actually bad for you is not subversion they think it is. You can find the same lesson in any Bible belt homily. At any rate, the actual contrast exists between the film’s treatment of the subject matter, and simultaneous insistence on its moral and artistic value.

For all of Fennell’s distaste for female anger, she considers female trauma to be the most appropriate home for her characters—from Cassie to Dean Walker to Madison. While the men suffer only reprimands, the most elaborate lesson plan is reserved for Madison, who Cassie gets drunk and hires a man to take to a hotel room. Both Madison and Dean Walker’s daughter are characterized as frivolous, superficial, and status obsessed.

Even if its failure to deliver on the rape revenge genre was just bad marketing (gleefully taken up by Fennell), even if the intent was to avoid genre conventions entirely, a film still has the burden of being a compelling feature on its chosen themes. Basic elements such as characters (flat), dialogue (cliché), motivation (inconsistent), structure (abandoned), soundtrack (exhausting), are all embarrassingly misused or ignored entirely. This film fails by the standards of not just genre, but the medium itself. The rewards and accolades that have followed are an insult to basic taste and audience intelligence.

Those who defend Promising Young Woman say the point was for it to withhold catharsis, that it offers a cynical intervention into our understanding of “nice guys”, revenge, and forgiveness. All of which is completely undermined by the film and Fennell’s own description of her film. As well as by the final scenes of the arrest and Cassie’s posthumous messages. The cynicism lies in the fact the movie is awards bait for an industry desperate to launder its image in the wake of scandal, and Fennell benefits from the opportunity to do so.

The positive reviews, which all cite the same opening scene, prove how much Fennell has relied on a “cool” trailer, and viewers projecting the film they’re being told exists. Promising Young Woman seems to want both the recognition and allure of feminist power while being driven by the traditional values of white femininity and an internal logic of female martyrdom. How traditional? The first and only time Cassie expresses any satisfaction, or even peace, is when she consummates her victimhood in the grave.

There’s nothing new to see here. The Western tradition, despite its violence, never suggests reparations and rarely recommends revenge. The Church preaches forgiveness—it’s all very “let he who has not sinned cast the first stone.” Which sounds a lot like what Ryan says when “confronted” by Cassie, “come on, haven’t we all done something we’d cringe at now?” For Fennell, I hope that’s limited to this movie.

Liked this ? Let me know by becoming a subscriber, or even supporting in kind through venmo @ayeshaasiddiqi

Some of the many potential choices available to the filmmaker:

Cassie, upon finding the video of her friend’s assault, reports it. The lawyer who once defended campus rapists tries to redeem himself by prosecuting his former client with the newly procured video evidence. But statutes of limitations protect the rapist, as they often do. Cassie, a skilled surgeon, feels compelled to take matters into her own vengeful hands. She mutilates men who prey on women they mistakenly consider drunk - doling out justice as she sees fit. She uses the fact she’s a pretty young white woman to remain safe from getting caught. The subject is treated with the gravity it deserves, has fun with society’s blindspots which are better observed without sanctimony, and the revenge is allowed to be as bloody as possible. To me, that’s the better movie.