Interview: Ana Fabrega of Los Espookys

We talk about her brilliant HBO comedy and making tv in the twilight of the streaming wars.

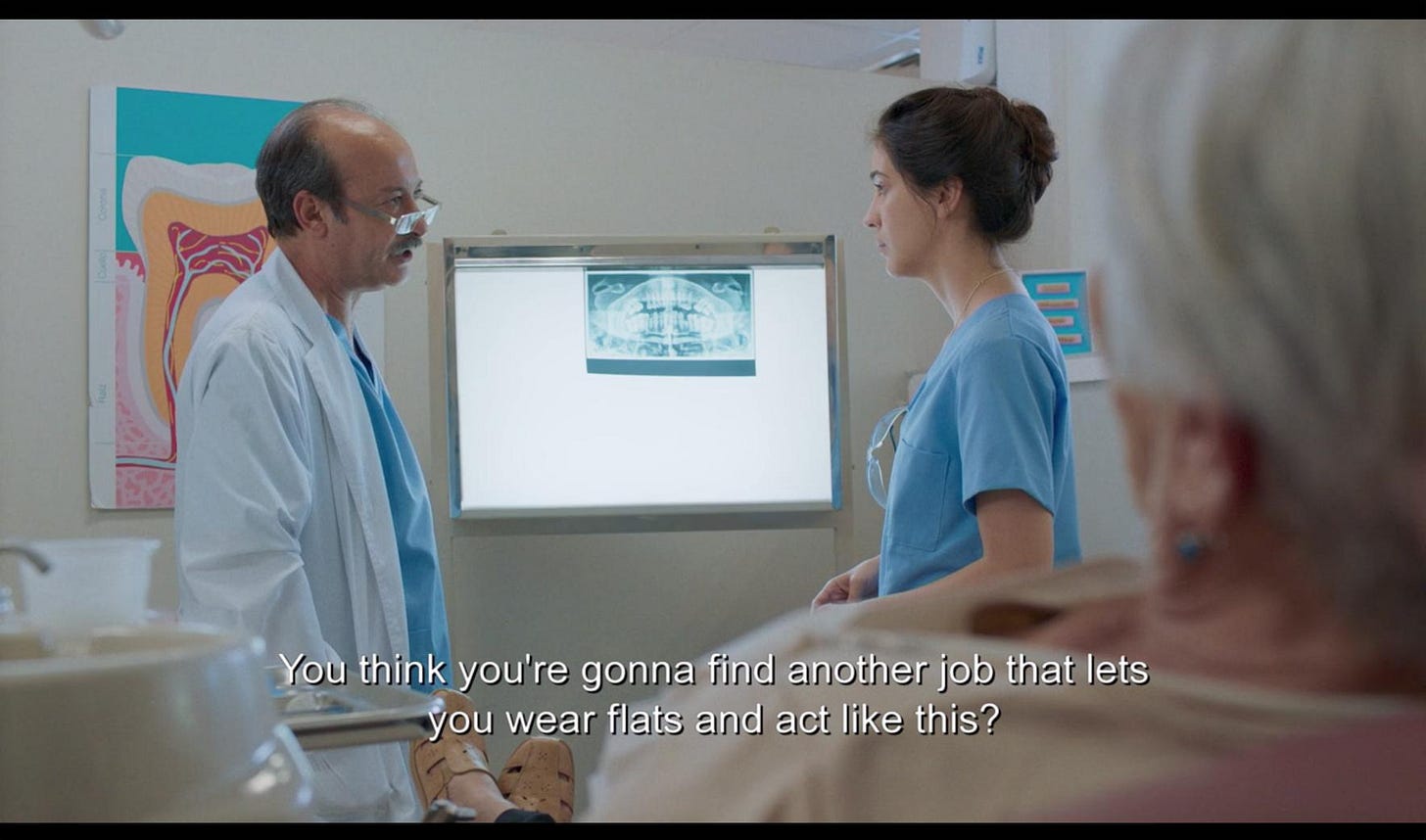

Since the series debuted in 2019, HBO’s Los Espookys has become a favorite for its stylish characters and wry humor. In the series, the titular group is contracted to help people meet life’s challenges. Los Espookys are who you call when you need help getting your grade school students to listen to you (by inventing a monster who dies because he doesn’t heed the teacher) or manage dissatisfied customers at a cemetary (by pantomiming the spirits of people’s loved ones who insist that actually, they prefer being buried at the incorrect grave markers).

In an unnamed Spanish speaking country Los Espookys carry out their missions with the seriousness of a consulting firm and the production value of kids operating out of a tree house. In their world, anything from a minor inconvenience to a drama of geopolitical scale can be resolved with the right macabre charade. But it isn’t all rope pulleys and paper mache. Demons and phantoms exist in this world too.

While much of the show’s comedy and drama lies in the juxtaposition between the truly spooky and the theatrics the group organizes, that’s not all it depends on. The jokes range from slapstick to satire on the US presence in Latin America.

The second season of Spanish language series is out now. I spoke with writer, producer, and actor Ana Fabrega, who—in addition to playing my favorite character on the show— has co-written every episode with Julio Torres, who plays Andres.

Ayesha: Something that I really enjoy about the show is that you wouldn't have to change a single thing if it were an animated series instead of live action. It has the joke pace and character design of a cartoon, is that intentional? What informed the feel of the characters and how they move through the world?

Ana: Yeah, we didn't set out to have it feel that way, but I do agree that it feels like a live action cartoon. It’s organic to Julio and I’s writing process. We have so much overlap in the things that we find funny, how we approach creating characters and building worlds, so that it feels like a cartoon is just a by-product. There wasn't anything that we necessarily set out to do.

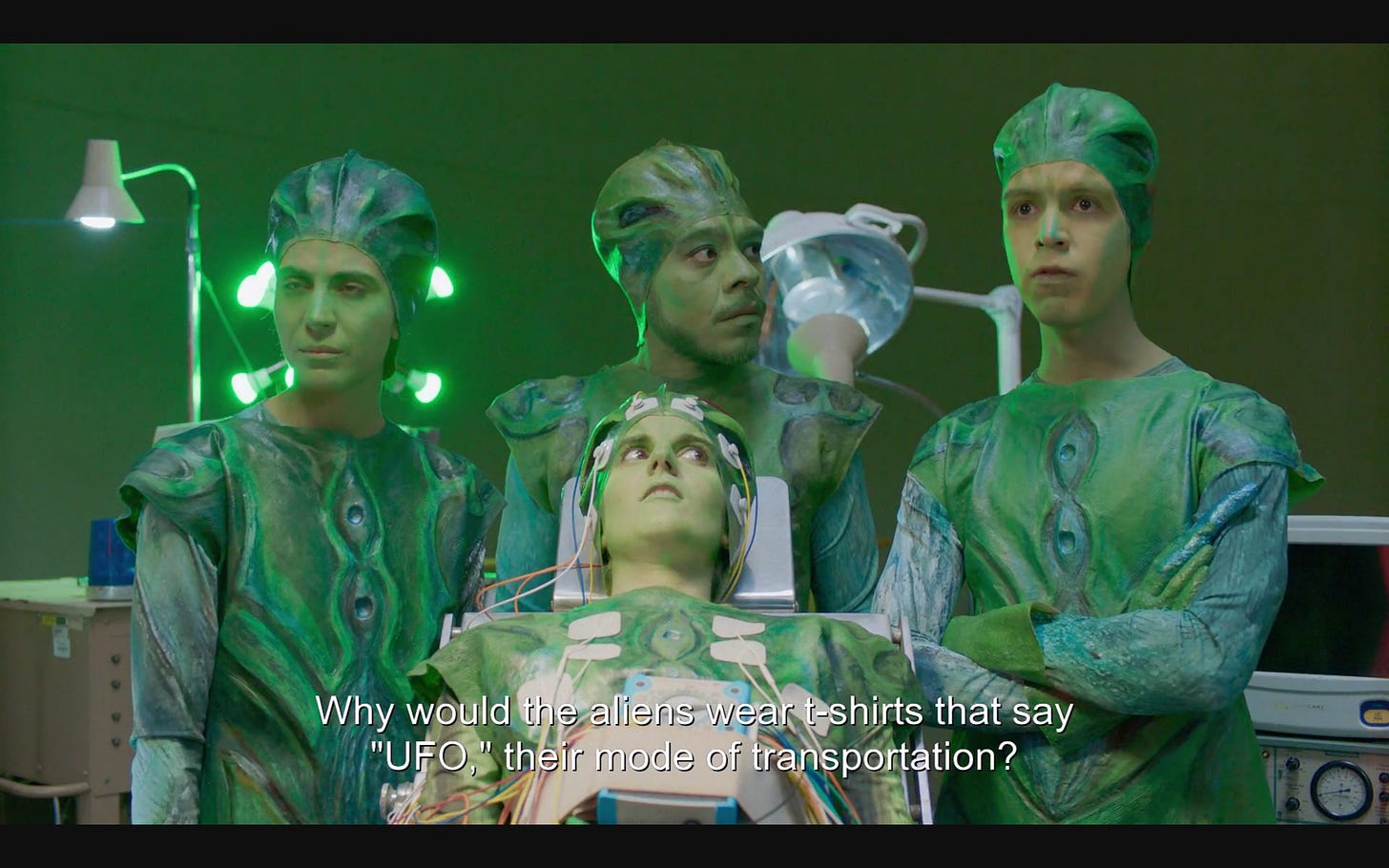

Ayesha: It's a very artful show. The relationship to practical effects that the show has feels of a different time, especially now, when so much of what's on our screens is super smooth, super slick CGI. Every set piece, every prop, feels recreatable in a way that's really charming. Could you tell me about your approach to practical effects and set design and how you achieved such a textured look?

Ana: I have to give credit to our designer, Jorge Zambrano. He brings so much to the writing. Julio and I are very visual. When we write things, we have really clear visions of how we want it to look. Then when we get down to Chile and Jorge presents us with his ideas after he's gone through the script he’ll always add more that we're like, “Oh yes, of course, that's just it.” He adds so much to the look of the show. And then the choice to do practical effects was—these people are doing little gigs on their own, they can't do a green screen. It is kind of funny when people fall for it, so part of it is also just that it’s funny. And then on a more practical level, just budget constraints—we don't have the money to do CGI. I think if we had really amazing special effects, it would be a different show.

Ayesha: Yes it’s very much in line with the suspension of disbelief required to be in a world where there are ghosts and the ability to talk to “the shadow of water.” It feels coherent to the logic of the show for people find the Los Espookys convincing. I would say it’s—and tell me whether or not this is accurate to say—it's very punch line driven, not plot-driven.

Ana: Yeah, that’s how Julio and I write. When we start writing the season we'll spend a few weeks just throwing ideas out for funny things that can happen... Or funny situations for a character to be in. And then once we're like, okay, all these things, then we figure out, how can I make a story out of it? It's almost like writing backwards. Especially because of the languages in the show. We know when we're writing people are going to be reading it. So is it funny to read it and does it sound funny to say it in the other language? It just creates a lot of opportunities for jokes.

Ayesha: So much of the creative arts in the last decade, everything from writing and performing, has been re-categorized as “content” and forced to compete on terrain skewed towards executives who treat the creative arts as another financial asset. How does it feel to be a creative artist in this era of media consolidation?

Ana: It is something I think about because I'm interested in the business aspect of entertainment. And I think that it’s awful that entertainment over the last decade has really come to be viewed as a way for people to make money, and you get all these hedge fund private equity people throwing money into entertainment as yearly revenues are going up at places like like Netflix. Then the second it dips, all the money exits. And then the people who are at these companies are all, “Oh shit how can we make profits? Well let’s cut costs.” So then suddenly every show looks the same. They don’t want to take chances. They want to do what they think is the safest bet. And you end up with all this TV that is so flat. And then people complain, “Oh, there's so much TV, but there's nothing to watch,” and it's like, yeah, because it's treated as an investment, not as art.

At Warner media when David Zaslav stepped in he said, I'm going to return 300 million dollars to shareholders. So cuts were being made at HBO Max. I'm sure you've heard about stuff being pulled and things like that. It's all just efforts to save money. The other side of it though, is there are some shows that have budgets that are more than double what our show budget is and it doesn't have any sort of aesthetic. It's just people in the city. And you're like, what are you spending all that money on? We make our show for so little.

It is, I think, very unfortunate to go in, especially when I've gone in to pitch things, to know that because I don't write things for “everyone”— or who they perceive to be everyone—I'm going get, “Oh it’s too niche and not worth the financial investment.” But I think that that line of thinking is only going to bite the industry in the ass. You see people now cancelling their Netflix because they're like, there’s nothing good on there anymore, you know?

Ayesha: Does it feel like Los Espookys got in just under the wire before these cuts started being made? There was a brief moment, with the way social media had pushed dialogue around race, executives seemed to have a sense of urgency around proving that they were aware of certain trends. Plus the industry was flush with cash as the emerging streaming platforms raced to compete with one another and capitalize on being seen as doing something “important” or aligned with social justice causes. Suddenly they were open to taking meetings with people who weren’t white men. I worked in TV development then and the white execs I worked with were very attuned to trying to find “non mainstream” creators. The moment ran the gambit from Reese Witherspoon and Apple telling “womens stories” to Netflix’s hiring then firing of editorial teams led by people of color. That keeness seems to have dissipated, the spending spree behind the “streaming wars” has cooled—like you said it’s now about shareholder returns.

I don't want to ask a question as pessimistic as whether Los Espookys could have been made today, but I do want ask you about what it was like having co-signs as powerful as Lorne Michaels and Fred Armisen. What was it like to navigate that professionally? Both you and Julio were very young when Los Espookys was being made. For your debut project to be shepherded by such expert figures, people who are taken seriously in the industry, what was that like to experience on your end?

Ana: It was in 2017 that Fred approached Julio and I to help him develop the show, and so yeah, I was like, 25... Or was about to turn 25? And yeah, obviously, if I had gone in to pitch the show no one would have bought it. They took the chance because Fred is Fred and has a track record of successful shows. HBO wanted to be in business with Fred and then obviously as Fred comes from SNL Lorne Michaels is involved. But beyond that, Lorne is not involved in the show. To be frank I’ve spoken with him once in my life. I met him when the show got picked up. We went and met him for a drink and that's it. When the first season came out, he said, “I like it.” It’s not like a hands-on thing. Even HBO is hands-off with us. While I don't think that anyone would have bought the show if just Julio and I pitched it, I think if today Julio and I tried to pitch it then maybe places that are eager to say, “we have representation on our network!” would have gone for it. It’s funny doing press for the second season compared to the first and having so many questions about like, “So you guys set out to make a latinx queer…” and it’s like, no—we didn’t. We just wrote the show that we wanted to make.

Ayesha: I’d love for you to say more about the degree to which the network and other producers were hands-off. Because it feels like you had the creative rein to make it exactly what you wanted. I’m curious to hear more about how you achieved that, were there choices you would recommend to other creators towards protecting their creative vision from network notes, which often aren’t always aligned with the goal of making the best show?

Ana: In a way, so much of making something is the right producers. We have Lorne Michaels and Andrew Singer who are big at the top of Broadway video. But our more hands-on, producer Alice Mathias had worked with Fred on Portlandia and Documentary Now, and she helped us get our line producer who was another huge important part of the equation. Yeah, it's not just the money, but having someone that understands what you want to make and your vision and can help you assemble the right team and essentially budget properly to do it is huge. Our line producer Nate Young and Sharon Lopez are people who really understood the show and were champions of what we wanted to do and helped us find the right people to do it with. Then the rest of it is just having the creative team, like the head of our art department and our VP and just all that stuff. When those pieces all align, it's so important. A big part of it is in the beginning just having the right producer who understands what you want to do and helps you do it in the best way possible. The producer is also helpful when you have something that you want to maybe push back on and you need someone in your corner. They are there to be your ally.

Ayesha: It doesn't seem like you and Julio are writing with any kind of mission beyond what you think is funny, but do you feel Los Espookys is in part of the lineage of Latin American magical realism?

Ana: Yeah, I see why someone would think of magical realism with the show. It wasn’t, like you said, something that we intentionally set out to do. It was just, we want Andres to be able to draw a circle and the moon appears. We’re both obviously Hispanic, and I think maybe subconsciously, a lot of that is kind of in our minds, but it wasn't yeah, something that we set out to do.

Ayesha: There are probably practical advantages to setting the show in an unnamed Latin American country. It exempts you from a degree of veracity. Some reviews of the show say it's an unnamed Latin American country, some say it's a fictionalized Mexico. It doesn't feel like the show is trying to make a claim for a pan-Latin American identity. It does feels like one place though, not an amalgamation of many. While it’s shot in Chile—were you drawing from different parts of Latin American culture in making the show? How important is it even for Los Espookys to be tied to the familiar and identifiable?

Ana: Initially, the pilot was set in Mexico. The show was initially called Mexico City: Only Good Things Happen. It was totally different than what we wound up making, and so that's where the Mexico City thing comes from. And then HBO wouldn’t let us shoot in Mexico. So we were like okay, if we’re not going to be in Mexico let’s not tie ourselves down to having to represent Mexico. Julio is from El Salvador. My family is from Panama. Our co-stars are Mexican. Our crew is Chilean. Let’s just have it be anywhere because we’re all from different places and then we were not so bound by representing any place authentically. It also opened it up too. Everyone's accents are different. We can have Chilean actors on, we can have Argentinian actors on, and it's fine that we all have different accents.

Ayesha: It was fun seeing Kim Petras in this season. I wanted to ask you about the decision to represent American political heads of state as early aughts archetypical blonde “bimbos”. It really does feel like an accurate extension of the Fox News Barbie news anchor and the famously blond and short-skirted aesthetic of right wing cable news anchors who are very often mouthpieces of the State. To close that gap and make them not just the mouthpieces of the State but members of the governing body itself, is really fun. Tell me about that.

Ana: When we started in season one we wanted to have an American presence in the country. The show takes place in Latin America so of course, there has to be an American influence there. And we decided it would be funny if she was like this Barbie that is not just a front man, but is the head of the whole operation. And then with the second season we wanted her to have a boss. So we were like, what's a more...elevated version of her? Ambassador Melanie Gibbons—also their names are so…just like, you know—she’s in cheap looking pink stuff and then her boss Kimberly comes in wearing Moschino. She’s intimidated by a higher end version of her. And together they’re like, “what can we do to extract resources” and it was just like, yeah, it's funny. And it's also like, true.

Ayesha: Could you tell me more about the actors who play Renaldo and Ursula and how they were brought onto the show?

Ana: Yeah so Bernardo Velasco plays Renaldo and Cassandra Ciangherotti plays Ursula. Cassandra we found through casting, and then Bernardo had worked with the director who shot the first season. And these were also done remotely. They were in Mexico at the time, we were just getting tapes. And we shot the pilot and immediately after meeting them, I was like, I can't imagine anyone else playing these parts—especially once we got to know them better. The brought so much to these characters and it really informed our writing going into season two. And then in real life, Bernardo is the sweetest guy. The things about Renaldo that are so sweet, that’s Bernardo. He always brings a little gift for everyone when we come back to Chile. Cassandra is also so sweet and funny and also really into the mystical. She told me, for example, that she was having a hard time understanding who Ursula is and then she had a dream, and then in the dream, we were talking about it, and then she was like, I know who this is.

Ayesha: I wanted to ask you about your character in particular. I recently watched John Early and Kate Berlant’s special, both of whom I'm also a fan of, and who also specialize in characters without self-awareness. John and Kate’s characters are un-self-aware, but super self-conscious and desperate to prove something. And in Los Espookys the characters are not self-aware and not trying to prove anything at all. Your character especially is so confident in—to comedic effect. I found that to be such a departure from the tone that I think dominates a lot of film and television right now that it almost takes a minute to acclimate to. It's a very chill frequency that the show operates at. And I felt watching it, especially when I watched the first season when it came out, almost needing to drop my guard a little bit, like relax into the show…American TV often feels very stressful. And this show isn't...

Ana: Yeah, so with Tati in particular, I just thought it was funny to be so confident and have no self-awareness. It then just leads to really funny situations and ways for her to react—to think that she really knows herself and how she's perceived, but it's so off. I think in general, sometimes in shows I feel like the comedic relief character that's clearly there to be the funny one becomes so over the top. It’s like every time they speak, they're saying, remember I’m the funny one! I find it insulting to the audience. People will get it, you don't need to spoon feed it to them. And I think the way you describe it, letting yourself settle into this show, it makes me happy to hear that. That is how people need to approach the show because at first it might be like, wait a minute, other shows that have worlds where the rules are so clear and it's so part of the story. For us anything that's kind of happening—just relax and let it unfold. And I think a lot of that is just trusting your audience. When Julio and I write, we're not like, Oh, what if people don't get it? It's like, you're going get it. There's nothing overly obscure. It's a pretty easy show to follow. And I think if people go into it with an open mind and they're down for the ride, we're happy to bring them along.

Ayesha: I really love Tati and in so much that’s written about the show she’s described as an idiot or someone that doesn't know what's going on. And I feel quite sympathetic to her, I think because I relate to her. Because she's not illogical, she's just operating with her own very literal logic. And is very comfortable with who she is and is enjoying her own version of life that may not feel totally accessible to others, but is valid to her.

Ana: Yeah, I think that on the one hand, yes—Tati is dumb, I think we can say that, but it makes sense when you follow her line of thinking. I thought it’d be really funny to have someone whose view of the world is obviously so informed by culture and what she's seeing. Like her idea of being a wife is, I wear the little apron and I cook for my husband. Everything that she has seen she has internalized as, this is how I'm supposed to move through the world and look at me, I'm doing a good job of doing it.

Ana: I think you've hit upon why I feel drawn to Tati. Because what you're describing about her logic being purely a result of the way she's encountered culture—I think anyone who has experienced being foreign in any place or come to a culture second-hand could relate to that process. Moving to America and being a kid in school, I definitely had a lot of Tati moments where I saw something on TV and thought oh, okay that is how you do the thing. Now I can just go to school and do similarly. And it was just….not accurate. There's so much you could explore about how someone arrives at their idea of things—which also feels like what the show is about on some level. Like what you were saying with why the American presence is represented the way it is. I think there is a bit of a dialogue between cultural archetypes and where they're formed in media and how they do end up shaping and informing people's lives in a way. You mentioned having your own personal interest in the economics of television making and you worked in finance before TV. Is there any part of you that would want to write about that world or explore it creatively?

Ana: I pitched a show in 2020—it took place at a time when there was a market bubble that was bursting for pumpkins in the 1800s. And that was a way where I was like, Ok cool, I can talk about things that interest me, because I genuinely have an interest in business. But also just in a very critical way. I listen to business podcasts and I read books about things like that. Because I want to know how things are working. But also to be like, those fuckers! You know? Initially it was just like, how do I do this? How do I play the game? And then over the years it’s like, wait a minute—this is bad. I haven't thought again about doing something that combines both. I think people who work in finance and then get into TV can be really up their ass about showing jargon that people don't understand, it's like who fucking cares? We don’t need to spend two minutes of dialogue talking about derivatives just to show it’s “real”. If I were to do something in that world, it would have to be of my version of it, not trying to portray it accurately.

Ayesha: I hope that's something we get to see. As Los Espookys shows, in many ways, you can achieve a lot through exaggeration that sometimes is more literal and cuts away the jargon.

Ana: That's what the whole embassy world in the show is. It's just really up front—we don't like what's happening here, let's intervene. And it’s like yeah, that’s what the US does. And it’s funny to see it said so candidly. In the show that I had pitched—that no one wanted to buy because it was too niche, and expensive because it was a period piece—part of it was showing this wealthy family that built up a bubble and got out before it burst. And very cadidly talking about, let's fuck everyone else and make a lot of money in the process, and then just be like, that’s not our problem. There is something fun about people being so blatant and saying things out in the open that they say in secrecy.

Ayesha: One of the things Los Espookys represents so well is the human desire to bend the world around you to satisfy what are ultimately very petty aims. In the world of the show, if you're a teacher that wants your kids to behave better then you can just hire a crew to discipline them through this performance of a monster — you can make children experience a parable. Tell me more about your position on the concept, because it’s approached with both sympathy and an awareness of the hubris of it.

Ana: Yeah, all the clients that Los Espookys have want something. And they're like, I'm going to get it. I'm going to find the way to get it and you're going to help me do that. Part of what makes me laugh the most in that episode with the teacher is when they come up with this idea for a little character for the kids to fall in love with—before they can even sort of make the pitch—she's like, he’s going to have internal bleeding. He’s going to misbehave and he’ll have to bleed internally. And it's this very violent thing that she wants the kids to see. I find that so funny because there are so many ways that you can teach this lesson that doesn't have to be violent like this, and you want them to see somebody suffering from misbehaving? And the way that Renaldo plays it—she's asking him, does it hurt? And he's like, “Yes, a lot.” It's very funny, but it's also violent. I can't believe this is what you want these little kids to be seeing, but it's just a means to an end. She's not thinking about the psychological impact of this on the kids.

Ayesha: And when she's pitching this idea to Los Espookys she has this glint in her eye—her fantasy is that if someone disobeyed her they would suffer... Which says a lot about her. The characters in the show are extremely honest about what they want. How connected is that to your own comedic sensibility and how you write? It sounds like you would deploy a similar approach in, for example, a show about the finance world.

Ana: Julio and I are so interested in the ways in which people, and this sounds so broad, are. The way that people move through the world and the ways in which they can be so, at times, not self-aware and then at other times be so like, “No, this is exactly what I want and I don't want to interrogate what this means.” And there’s something very funny about people like that. I think a lot of people are, or can be, like that. A lot of the people that Los Espookys do jobs for are like that. The professor that's like, hey, my kids are offended that I said this in class, can you just help me to get them to shut up, basically help me trick them and think I was right? This effort to take shortcuts and not interrogate—that's something that we're both very drawn to in our writing, individually and together.

Ayesha: The opening scene of season two captures a lot of what we're talking about, with the sculptor who's clearly failed at the assignment of creating a sculpture that looks like Shakira. And her response is to try to convince people that she is actually correct by hiring Tati to impersonate a version of Shakira that looks like the sculpture. That kind of doubling down feels representative of how people act today when social media can make them feel so cornered quickly. When that happens, very often the route people take is the one most like insisting, no I’m not wrong—this is what Shakira actually looks like. You see it play out in a very funny way in the show. But you see it happen all the time in real life. I think of JK Rowling and one day someone @’ing her on twitter, questioning her. And now five years later, that self defensive impulse has become a very real investment in a cause she feels personally implicated in, despite not having the same stakes as the people she’s positioned herself against.

Ana: People are so defensive and they're so quick to double down and dig their feet in. To say “No, this is what I think, and I refuse to believe that it's incorrect or that there could be any other point of view.” To go to the extreme of like—well, instead of this sculptor apologizing that they did a bad job, they’re going to show you that they did it right. And then it’s funny that people believe it. That's what's funny to me in the show is that there are no consequences for these kinds of bad behaviors. People hire Los Espookys to trick, to deceive, and it works out for them. There's no kind of moral reckoning for them, which I think is funny.

Ayesha: It's so funny. And also part of why it feels like, one, you need to acclimate to the show’s tone, and two, very relaxing once you do. Because it's a break from a world in which those kinds of attitudes do lead to consequences. It gives you space to live in the absurd humor of that type of self-interest.

Ana: Yeah and I think a lot of TV now is really obsessed with this idea of showing the morally right thing to do—portraying the world as good people and bad people. The world is grey, it's not black and white. It’s harmful, in a way, the extent to which certain shows can be very, “we’re gonna show people that we’re good” and then people watch it and think “I think like that too—so I’m good, I’m actually really good.”

Ayesha: It’s influenced how people engage with even fictional narratives and what being a fan of, or even consuming something, allegedly says about you. And Los Espookys feels like it can puncture that conversation because at its heart it’s about how goofy people are. 90% of our motivations are very silly. It makes me laugh thinking about someone promoting Los Espookys as being important “queer representation” because the queer characters do things like mislead people about why their loved ones are in the wrong graves.

Ana: Yeah that sort of social media thing of like—let me show the world that I'm good because of these things I might watch or whatever. And Los Espookys does not invite anyone to go, “look I support queer art.” Because that's not the show’s agenda, and some shows it feels so clear that they're written with this intent of like... Let's show how good we are and how much we know. And it makes for TV that thinks it’s saying so much, but it's saying nothing.

Ayesha: I imagine that the show and the way it was executed really benefited from the people closest to it being free from having to see it that way, because they're already within those identities. There’s no self-consciousness or forced posturing about it. There's so much you probably didn’t have to name because it could be taken for granted.

Ana: Yeah, I mean, I think that we got really lucky that we have a bunch of our friends acting in the show, so obviously they get it. And then our crew in Santiago, all the department heads and their teams for the most part, really got it. I feel very fortunate for that, because I do think that there's a world in which we could have had a crew that was like, why are we doing this? What is the show?

Ayesha: The show supports queer people and people of color in that it has created jobs for those people in the industry at a level where they can exercise some agency and remain authentic to themselves. But networks want the conversation regarding equitable representation to be limited to capitalizing on market demographics—because that maintains networks as beneficiaries—when it’s actually about access to opportunity, which would hold them to a different type of commitment. You mentioned a little bit of difference in the press cycle and the conversations you've had about the show, between season one and season two. What's it like promoting the show right now?

Ana: Yeah, so with the first season, we felt like even the HBO people weren't quite sure how to market it. And I understand because it's in Spanish and it's queer but it’s not just that. And when they pitched us their plan, it was just... if you speak Spanish, you'll like this. But just because people like a random show that’s in Spanish doesn’t mean they’ll like our show that’s in Spanish. And so I feel like after that, we were like, okay for season two we gotta be a lot more targeted—and make it clear who we think likes the show and who we've seen respond to the show. And it is people that are like, art people, a lot of fashion people, a lot of film people. We've been trying to be clear in the marketing plans let's not just go for “Hispanic” and “queer” because that's not really going to get us the audience we're looking for.

Ayesha: Yeah, it goes back to avoiding reducing art to this semaphore of listing off identity positions, who is that ultimately serving or what is that informing? And the answer is just…marketing. It’s training an algorithm.

Ana: Yeah it’s people patting themselves on the back for saying, look how good we are for having queer Spanish people. The show is very specific and we need market it to those specific people, and then also just aside from that. I felt like... Part of why I wanted to reach out and talk to you is because I wanted to talk to people that are also covering things in the entertainment world, but aren't going about it in the same way that all these other places do, who have different audiences that are probably going to be drawn to the show. Just go outside the box, because I think that's sort of what the show requires.

Ayesha: Los Espookys doesn’t require a lot of reaching to recommend— it’s genuinely funny and fun to watch.

Season Two (and One) of Los Espookys is available now on HBO Max. My thanks to @Anafabregagood for speaking with me and @espookys for the S1 show stills.